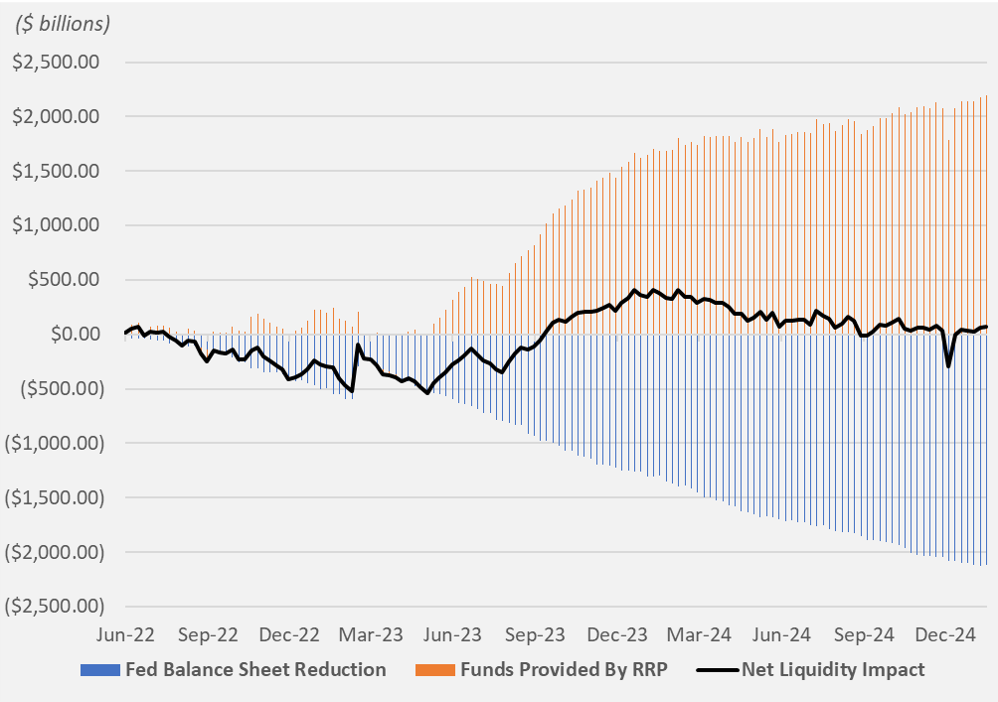

Ostensibly, the Federal Reserve has reduced its balance sheet by $2.1 trillion through nearly three years of Quantitative Tightening (QT) — a supposedly hardnose effort to tackle inflation by shrinking the base money supply.

The reality is less impressive. Rather than shrinking the base money supply, the Fed has simply mopped up trillions in excess liquidity, already sitting inert in its own accounts.

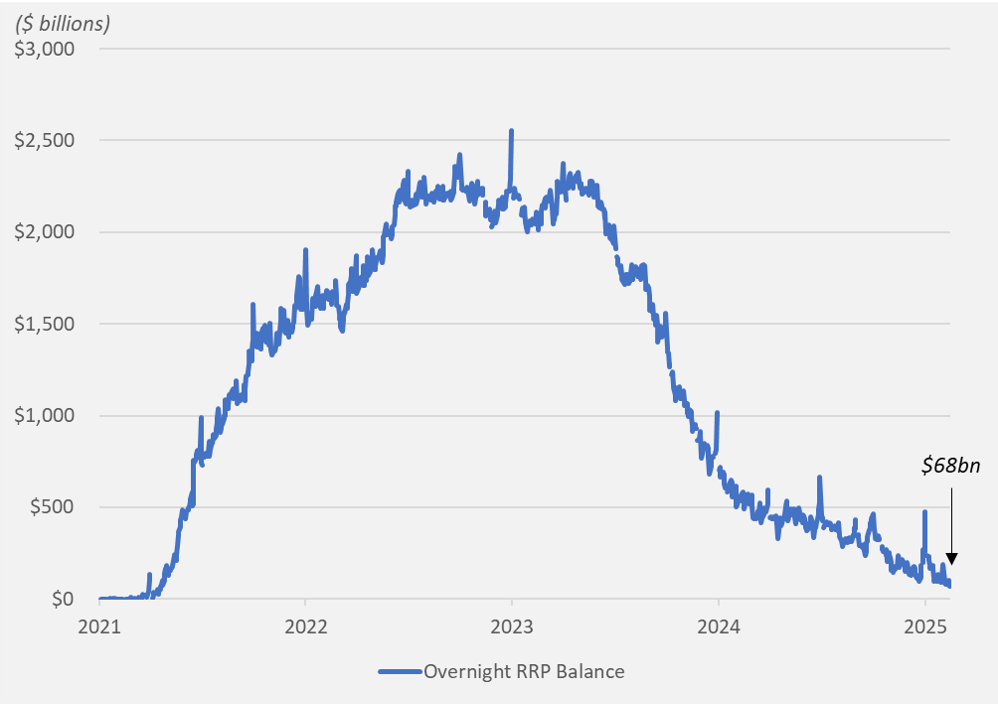

Since QT commenced in June 2022, usage of the Fed’s overnight Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) has decreased by $2.2 trillion — fully offsetting the balance sheet reduction. Over the same time, the monetary base, a more meaningful measure of dollars in circulation has actually increased. Reserve balances at commercial banks have increased marginally as well.

To date, the Fed’s QT program has merely moved money from the right pocket to the left. The decline in its aggregate balance sheet is an illusion — the elimination of double counting more than a true shrinking of money supply.

But the overflow tank is running on fumes. With just $68 billion remaining, the RRP now stands at its lowest level since early 2021. As it trends towards zero, so goes a vital liquidity backstop for financial markets.

Unfortunately, commentary on this topic tends to get reduced to extreme proclamations — imminent disaster or a total non-factor. Let’s cut through that noise.

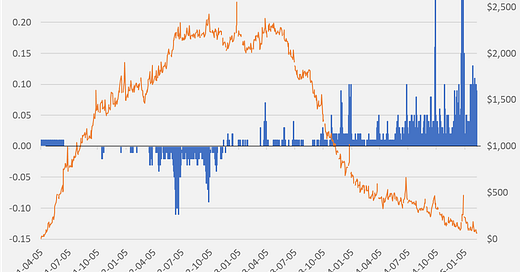

The exhaustion of the RRP does not spell disaster but it should not be ignored. Moving forward, QT will actually begin to tighten — reducing banking liquidity, increasing banking leverage, and increasing pressure in short term funding markets. Indeed, we have already seen increased volatility in short-term interest rates over the past several months as the RRP has dwindled.

Even still, the Fed’s plan to reduce bank reserves to the lowest comfortable level of reserves (LCLOR) suggests that QT is not done yet. Instead, QT may actually begin to bite.