EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Recession, or “The R-Word” as the financial media likes to call it, has become more of a threat than at any point since the Fed began hiking rates in 2022. For the first two years of that cycle, Fiscal Policy and Monetary Policy engaged in a sort of beautiful dance whereby the efficacy of interest rates in slowing the economy was blunted just enough by the supportive nature of Fiscal Policy.

Now, however, the fiscal impulse has turned decidedly less positive and the chances of a recession have risen. Rather than bandy about meaningless probabilities (I recently saw one forecast that said the chance of a recession in the U.S. this year is 50%, which is potentially the least useful thing I’ve ever read), I think it’s more interesting to explore something a bit more nuanced.

Recessions are not all identical. They each have their own unique characteristics and drivers. If the current uncertainty snowballs into economic weakness, what becomes the defining characteristics of that slowdown?

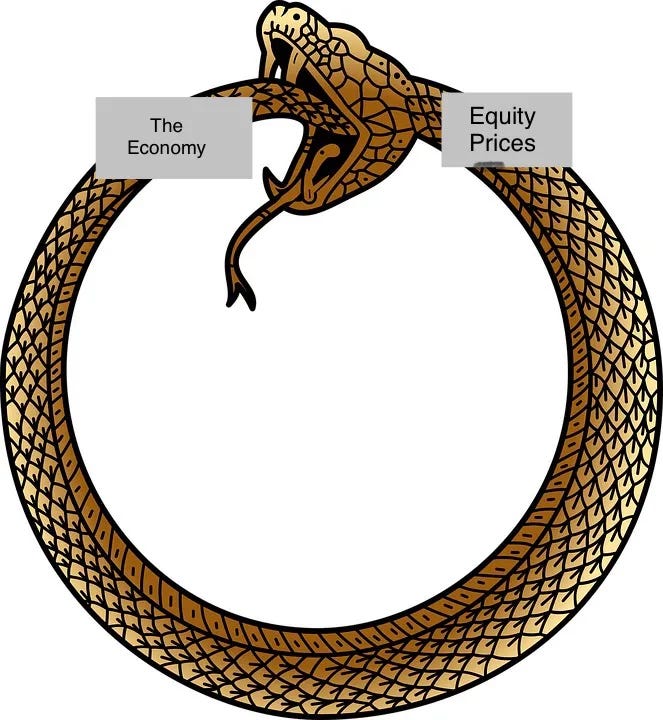

Despite appearances, the American economy is experiencing an unprecedented bifurcation. It’s a tale of two economies operating in parallel but divergent realities. A vast majority of wealth has accrued to the top 10%, and their exposure to the market makes declines a significant threat. A fundamental restructuring of consumer spending power following the pandemic has created both systemic vulnerabilities and unique market dynamics based on how this could play out.

A Wealth-Effect Driven Recession?

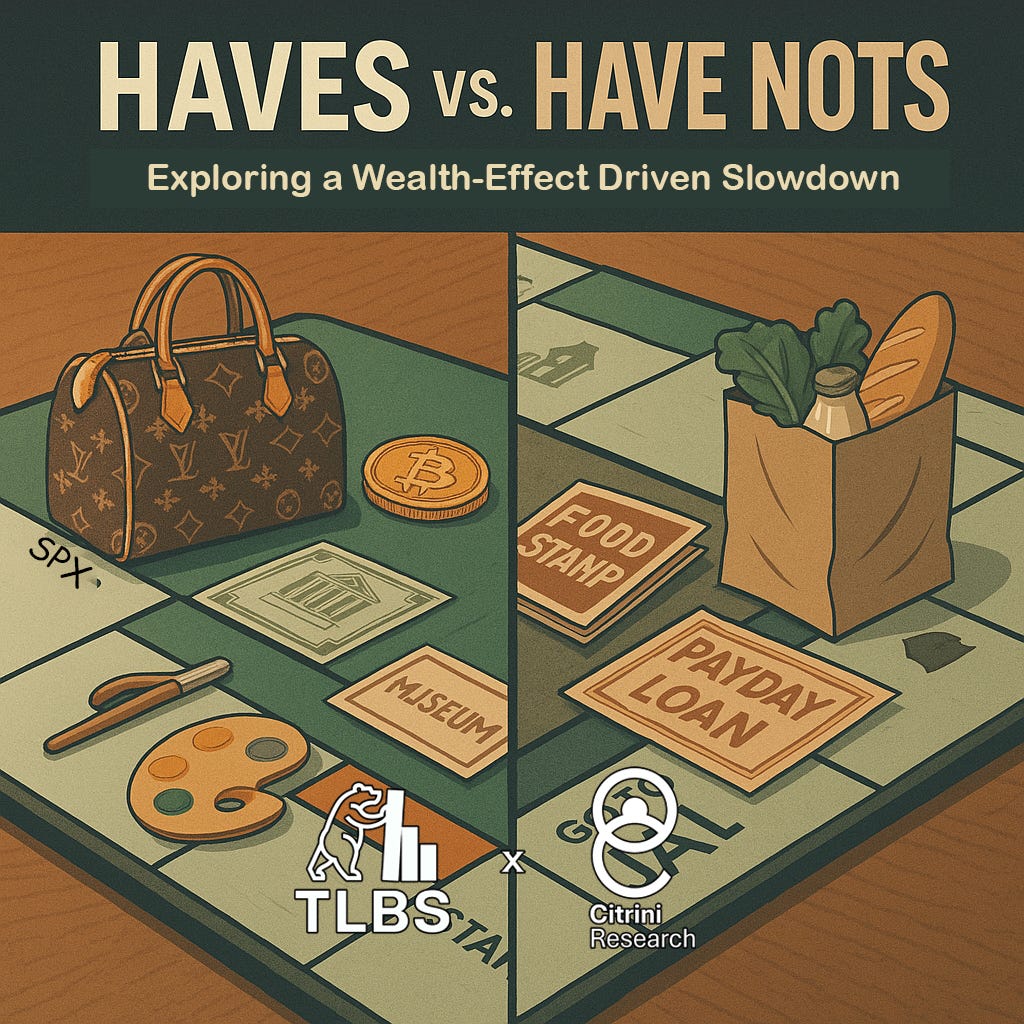

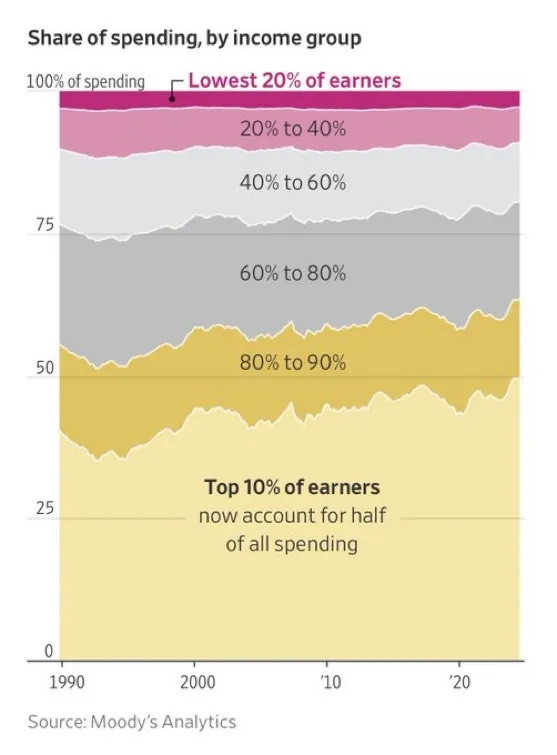

Citrini Research’s latest Macro Memo (After the Trump Bump) introduced the concept that the divide between rich and poor, in terms of both asset ownership & spending, had gotten so stark that the primary threat to the economy has become a decline in asset prices & a wealth-effect driven recession. With the top 10% representing half of all consumer spending (a statistic that is likely lower than reality considering the mechanisms of wealth transfer), this “Macroeconomic Ouroboros” seemed worth exploring further.

As it stands today, the wealth of the U.S. has never been so dependent on the stock market. Nor has financial wealth been so highly concentrated among the top economic percentiles and overall spending so dependent on those few. Therefore, it stands to reason that the economic prognosis has also never been so contingent on the movements in asset prices.

We often assume that stock market performance reflects the underlying economy – some blend of jobs, consumption, investment. Of course, there’s feedback – rising asset prices can boost confidence and consumption, while falling prices have the opposite effect. But this reflexivity is not constant.

Valuation, asymmetry of outcomes, and the relative dependence on asset prices for ongoing economic activity must play an important role. Sometimes the economy drives the stock market, sometimes the stock market drives the economy. We believe we’re firmly in the latter dynamic.

A Government Policy Driven Recession?

Four years ago, the Last Bear Standing shined a light on a $50 trillion asset class that put one of the world’s largest economies on the brink. The Chinese property market – the economic growth engine of the country for two decades – was entering a policy driven collapse. As the primary store of wealth for much of the country, the property bubble’s deflation would have severe knock-on effects for consumer sentiment and consumption. Four years later, the Chinese economy still stands in the shadow of this property downturn, even as the re-routed investment is already bearing clear fruit.

Today, a different $60 trillion asset class is at risk. For the past fifteen years, the U.S. stock market has been the greatest driver of “wealth” in the world’s largest economy (indeed, in the entire world). Rising asset prices have boosted consumption habits from the top earners, even as the uneven distribution has driven social discontent and populism. And despite the many lessons of history to the contrary, there is now an engrained assumption of policy-based protection.

While it’s almost certain that an economic recession would coincide with falling asset prices, it also seems that falling asset prices could cause a recession. Perhaps it is even a prerequisite. Like China, an abrupt pivot in policy stands central to this question.

What if the Trump administration is serious about “Main Street vs. Wall Street”? With so much of the wealth and spending concentrated among the top 10%, it seems likely that any change in their spending habits could be enough to trigger an economic contraction.

From a political perspective, we have a defiant and emboldened President with populist-tendencies and a consolidated power structure who is intent on driving a new economic vision focused on protectionism, closed borders, and the retreat from free trade.

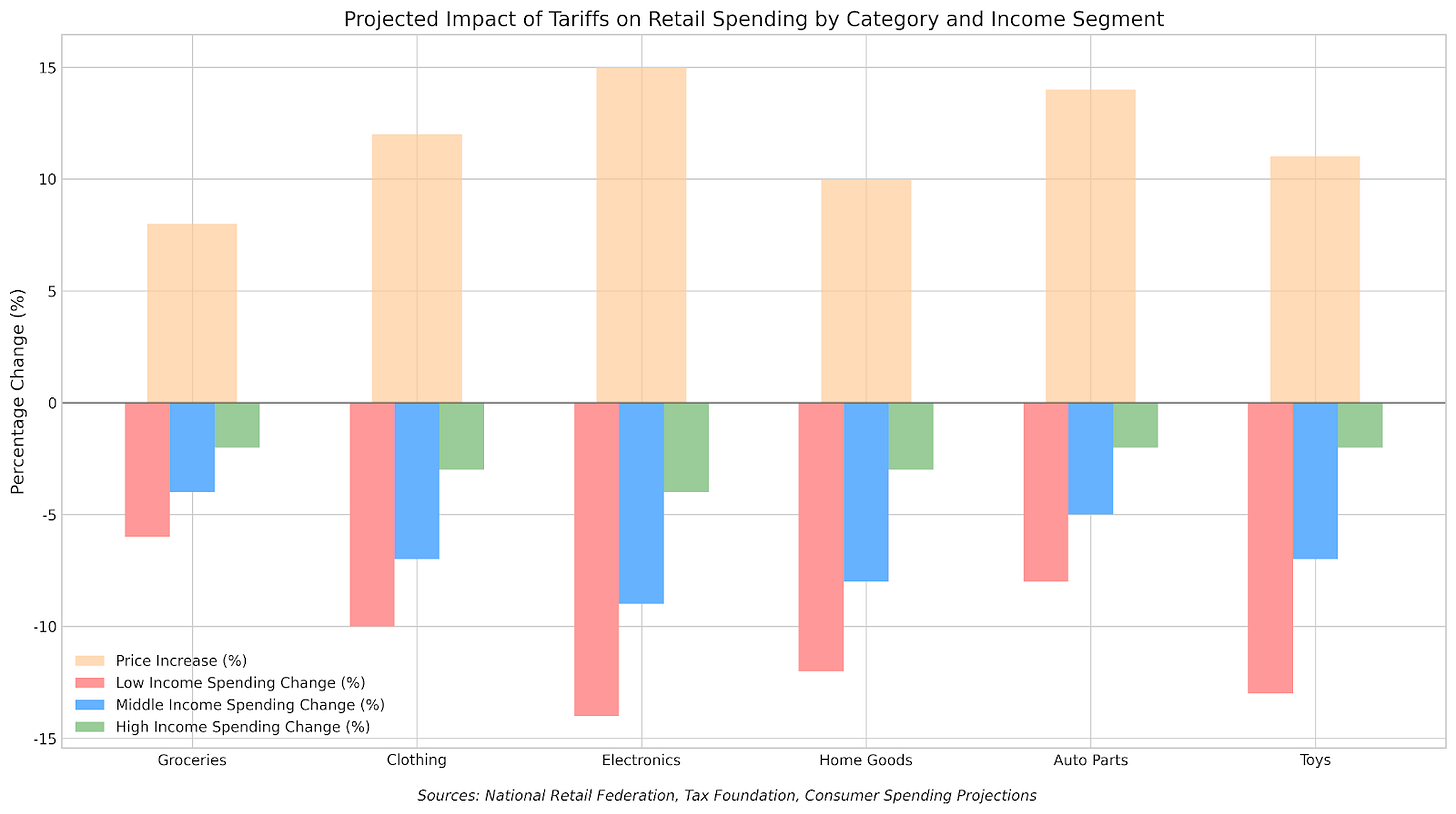

Undoubtedly, tariffs have a greater impact on low and middle-income consumers than they do on high-income consumers.

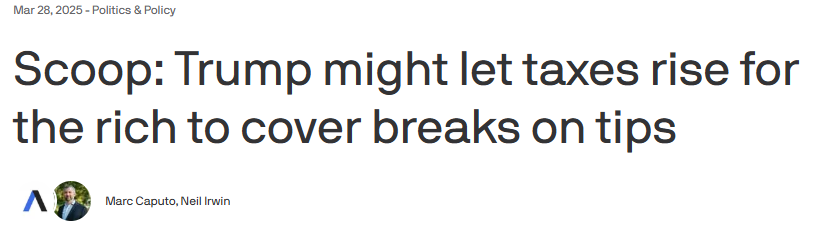

Even while writing this article, we were hit with this headline right after a terrible Friday for stocks:

Economists can debate the net effects of Trump’s proposed policies (and the pressures of his billionaire backers), but when he blames a falling S&P 500 on “the globalists” we shouldn’t ignore the class-based tenor.

And maybe he’s right – is there a greater emblem of the neo-liberal free-trade world order than the S&P 500?

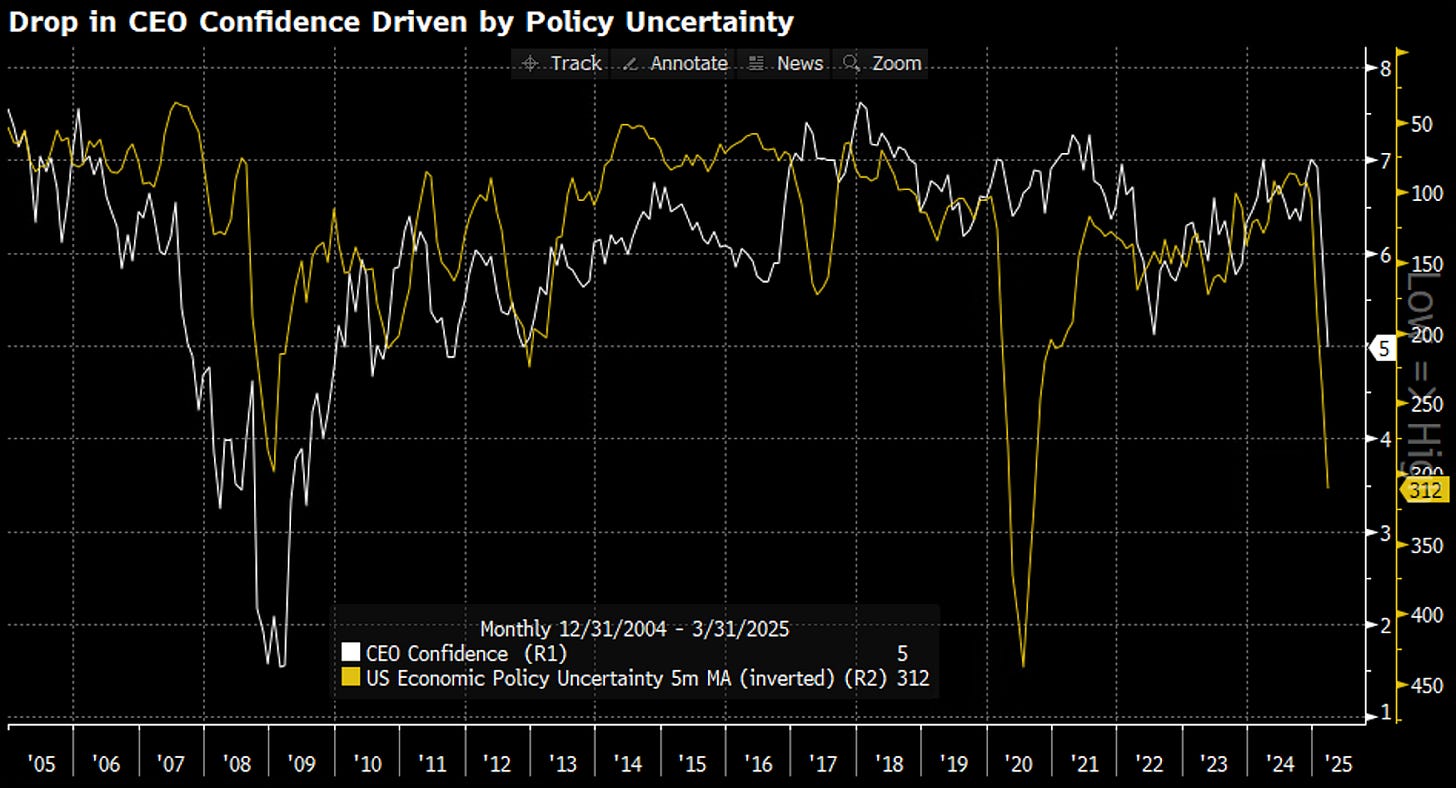

So far, it’s been a decent idea to listen to the administration when they say they’re focused on something. Already, we’ve seen the total suffocation of illegal migration, an enormous supply of cheap (and legally unprotected) labor for the prior four years. Tariff policy waffles daily, but as we laid out in our piece “Tariff-ied”, don’t expect Trump to retreat before a significant impact. Even in this uncertainty, trade tensions have grown and business decisions remain paralyzed.

On the other side..no taxes on tips? There are very few financial analysts, attorneys and accountants making tip income. Meanwhile, Trump’s Musk-shaped federal hatchet has already begun to hack at government employment and white-collar contractors.

An AI Powered Recession?

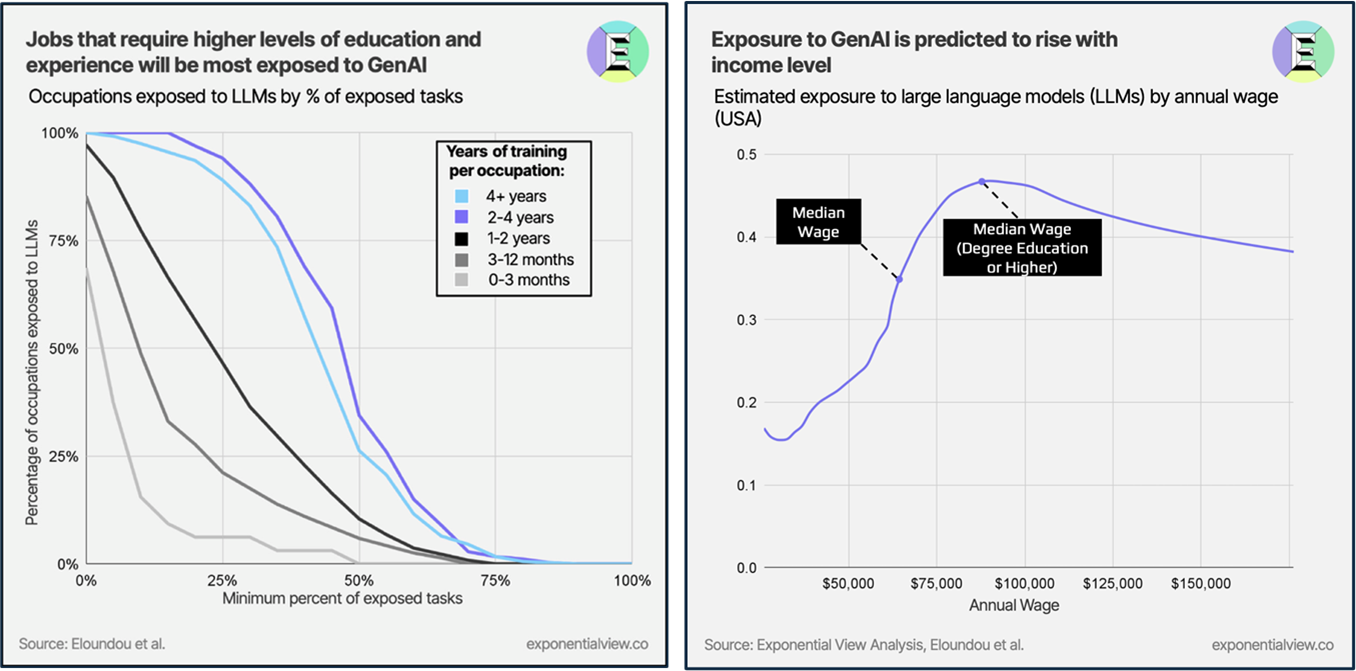

At the same time, a large-language-model shaped Sword of Damocles now hangs above the white collar employee.

If you’re a company that primarily employs these kinds of well-educated knowledge workers that has to go from simply pausing hiring due to economic uncertainty to actually cutting your workforce due to economic hardship, well… AI might not be great right now, but it just might be good enough.

What does “good enough” mean? AI has progressed just far enough–to the point where companies, out of necessity, will be willing to underwrite the risk that it can make mistakes or be sub-par at certain tasks and actively seek to implement AI solutions that can result in permanent job-losses for white collar professionals. AI systems are advancing most rapidly in domains that have traditionally commanded premium salaries - legal analysis, financial planning, executive decision-making, and specialized consulting.

Some illuminating statistics from The White-Collar Recession 2025:

The American Bar Association noted recently that the nation’s largest law firms have cut entry-level hiring by nearly 25% compared to previous years.

Ad agencies are cutting creative and copywriting positions as generative AI produces marketing materials faster and cheaper. Notably, even Grammarly—a company founded on augmenting human writing—laid off 20% of its staff, explicitly citing AI’s growing capability to autonomously perform editing and writing tasks.

Vanguard reports that hiring for positions paying over $96,000 annually has reached a decade-low level.

On the other hand, we’re a long way away from people who work with their hands getting replaced by AI. Jobs requiring physical presence, situational adaptability, and human interaction remain less vulnerable to AI disruption. From healthcare support roles to maintenance services, these middle and low-wage positions often involve skills that remain challenging for AI to replicate. We might encounter a temporary inversion of the traditional economic hierarchy as it relates to income & recession resilience in this first era of the “age of AI”.

High-Income Dependency

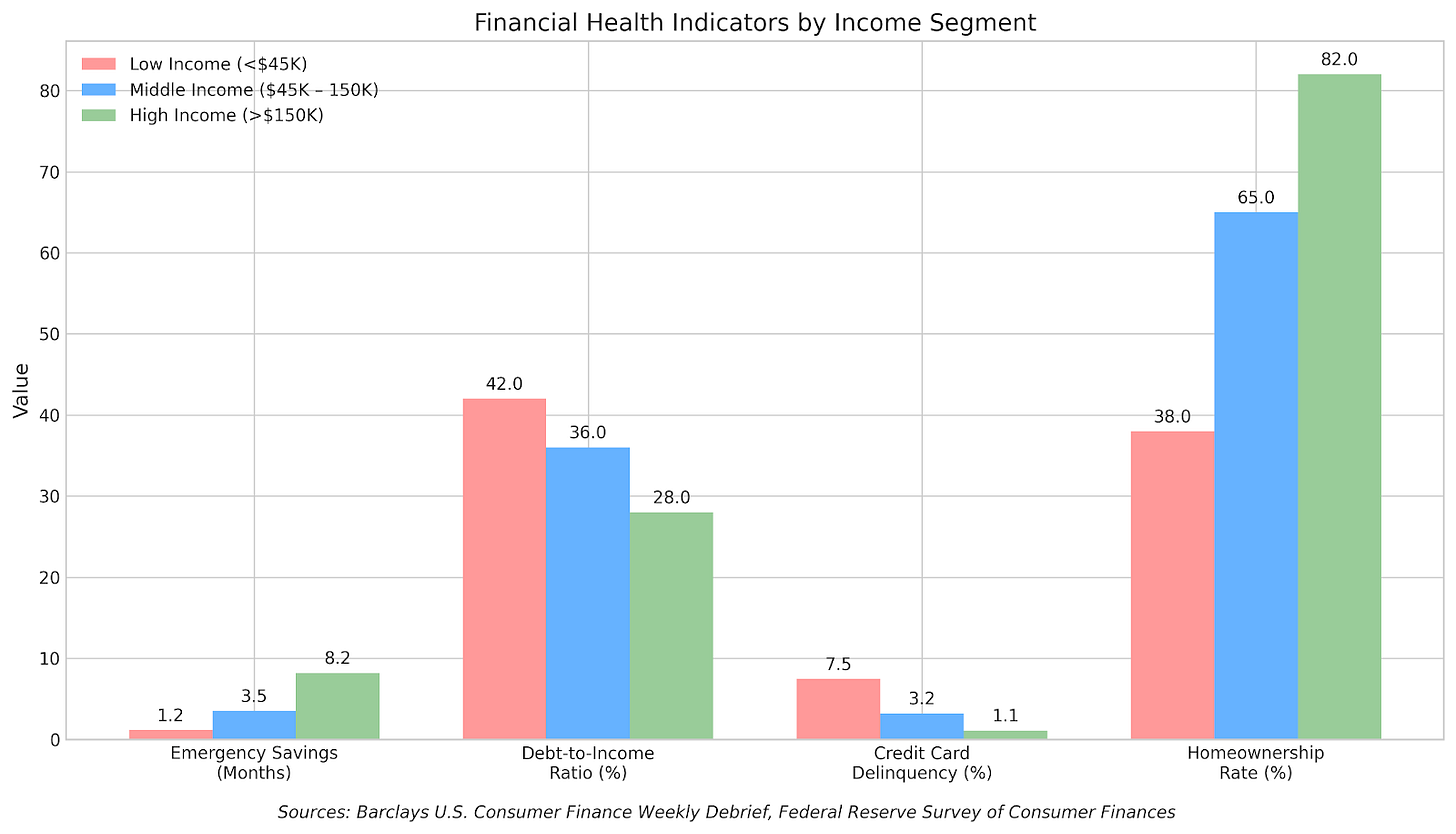

As we mentioned earlier, top earners drive both an outsized portion of total spending and discretionary spending. They are also highly disproportionately invested in financial assets.

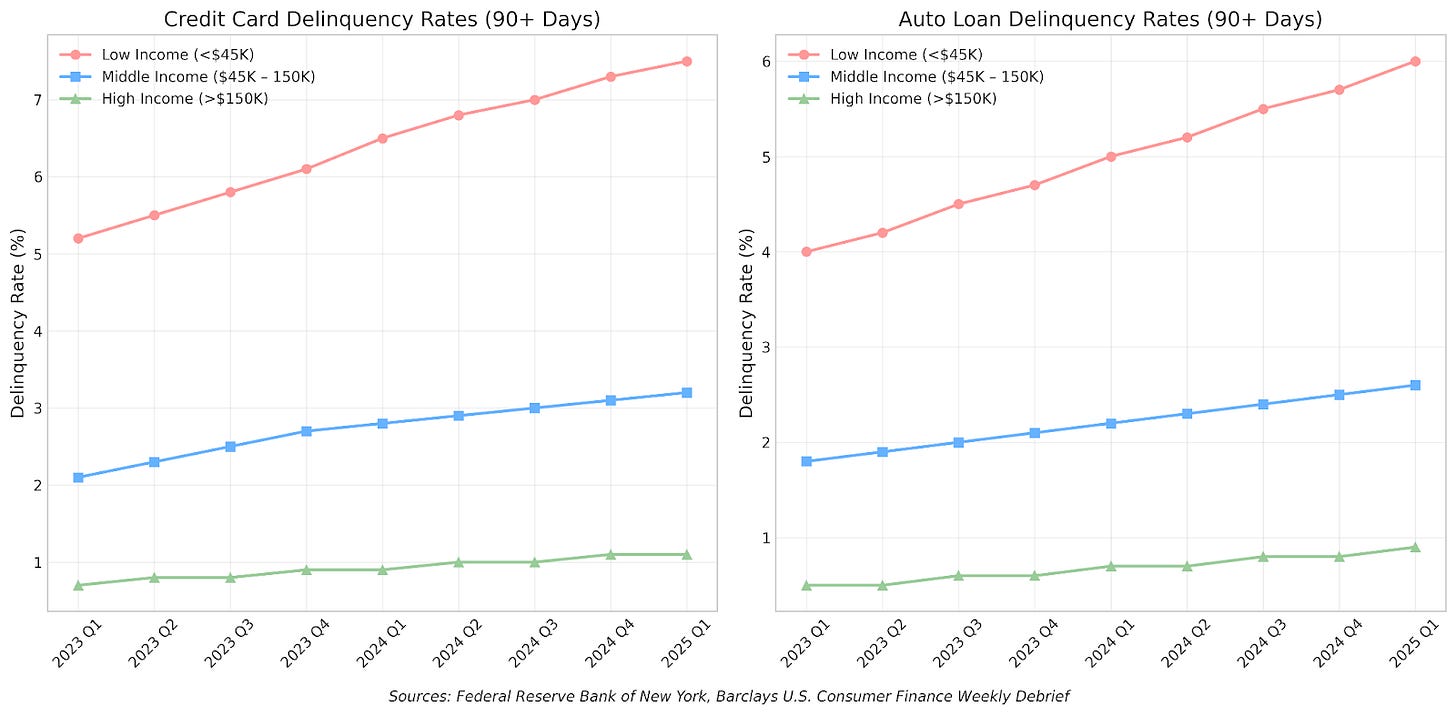

The top 10% of earners now account for approximately 50% of all consumer spending in the United States. Meanwhile, the bottom 90% have had their savings systematically depleted due to the impact of inflation. This concentration of spending power creates a precarious economic dependency on the financial health and sentiment of high-income households.

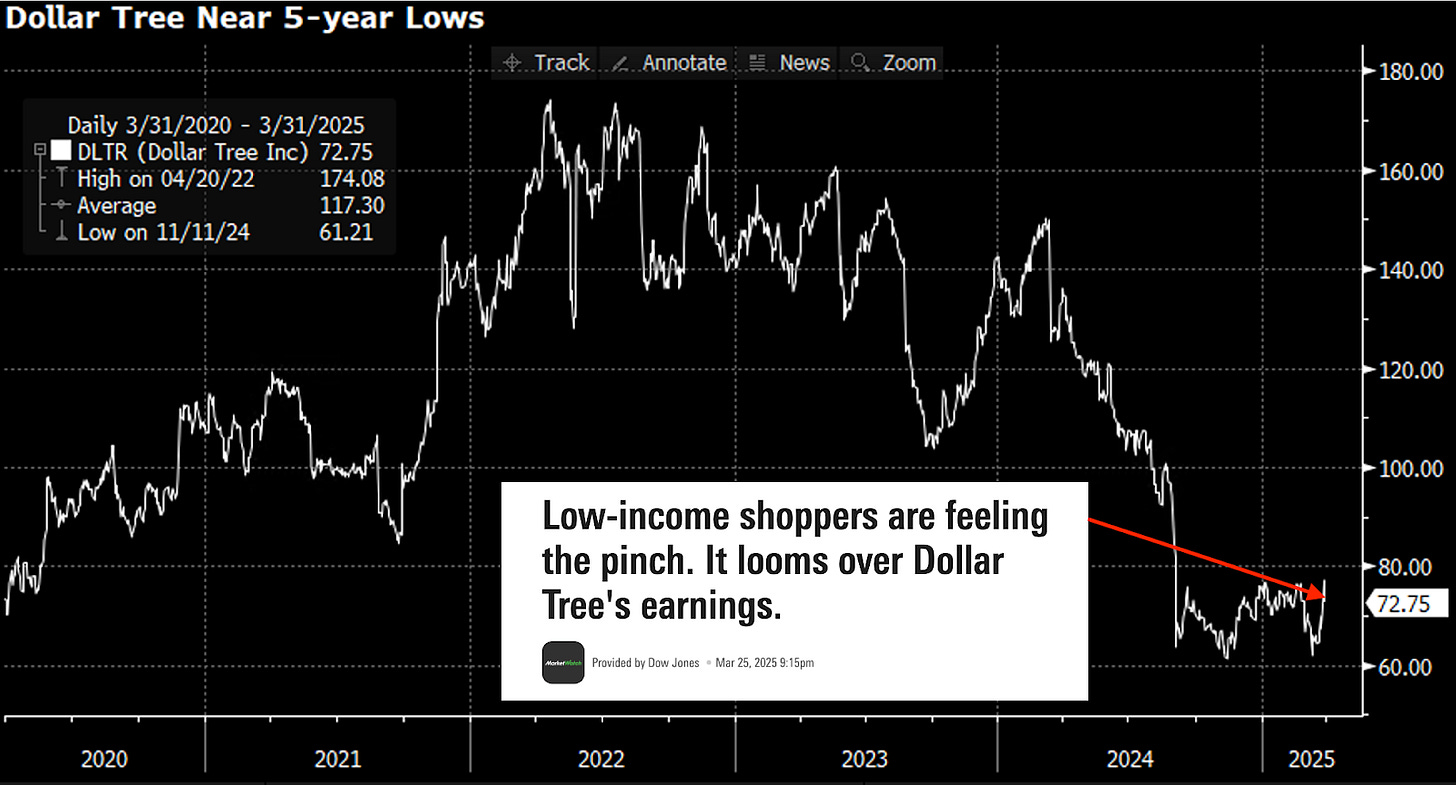

Low and middle-income consumers have effectively already been in a recession for some time, which is already reflected in the market.

Depressed consumer sentiment readings and a rejection of the incumbent administration reveal this reality even as headline numbers flash green. Inflation has had a significantly asymmetric impact on their financial well-being. Their spending habits have already adjusted. If we were to have a recession, the largest delta in spending behavior would likely come from high-earners.

Even in a market crash, top earners will continue to outspend the rest. But their relative spending decline could be significant — base-effects matter in year-over-year corporate profit growth. It seems like we’re approaching a tipping point where either spending patterns rebalance or social tensions around income inequality intensify (think French Revolution).

The culture of institutional Wall Street — dominated by top 10% income earners — creates blind spots, and therefore market opportunities. Given how lopsided financial asset ownership is, market participants are prone to become disconnected from the economic reality of most Americans.

A Divergent Recession…And How to Play It

All of this leads to an uncomfortable but (we think) well reasoned conclusion.

A sustained market drawdown could trigger a negative feedback loop that transforms financial market stress into real economic contraction through reduced high-income consumer spending. This transmission mechanism operates through direct wealth effect, psychological contagion, income effect, and housing market channels and, in terms of rate of change, will disproportionately exercise its impact on the economy through the spending of high income/net worth individuals vs low and middle.

A mean-reversion in spending patterns by top 20% vs bottom 80% would catch many companies on the wrong foot. After the spending from “aspirational consumers” (LVMH’s word for poor people with a stimulus check) was exhausted, many companies have focused primarily on their higher-end segments in a phenomenon dubbed “premiumization”. This targeting of the highest earners has worked well. The market has rewarded premium-focused companies with handsome multiples, while companies geared to lower segments are often pricing the recessionary conditions their clientele have already been facing for years.

But this article is not another exploration of how necessity spending is more resilient than discretionary spending in a recession.

We are exploring something else — what would the dispersion of stock-specific returns look like if a wealth-effect driven recession were to occur that had a significantly more pronounced impact on the “haves” compared to the “have nots”.

We’re not proclaiming that things would get better for the poor in a recession. However… the rate of change on the spending of the well-to-do would make the changes from the poor pale in comparison. The lower middle class is already in a recession while the upper class has been doing great.

While there’s some defensive and value aspects to this strategy, it’s unique relative to the classic recession trades. This isn’t just long staples/short discretionary — we believe any economic turbulence that caps off this cycle deserves more in-depth work than that.

Long Basket: companies either relatively insulated from wealth effect pressures (focused on value positioning, trading-down beneficiary potential, and necessity-based offerings) with asymmetric exposure to the working class and/or the potential to recover from years of underperformance due to their primarily lower-income focus

Short Basket: companies with high sensitivity to wealth effect dynamics, characterized by premium pricing strategies, limited trading-down defense, and disproportionately impacted by a stock market decline

The benefit of this approach is that it could navigate either a unique recessionary dynamic or a recovery in low-income spending and a narrowing in income inequality. In other words, it doesn’t require a bone fide recession for this basket to work. Our "Haves vs. Have Nots" investment thesis represents an asymmetric opportunity to capitalize on the economic divergence between high-income and low/middle-income consumers.

(Bonus Point: if you’ve just read all of the above and your reaction is that this is total nonsense, that there is no way the poor are less negatively impacted than the rich by Trump, that any potential economic weakness will be destructive for low and middle-income while being neutral or even positive for higher-income (as it has done many times before), then you can “choose your own adventure” and invert the longs vs. the shorts!)

This project is a cross-publication collaboration between The Last Bear Standing & Citrini Research. You can follow this link to subscribe to CitriniResearch.